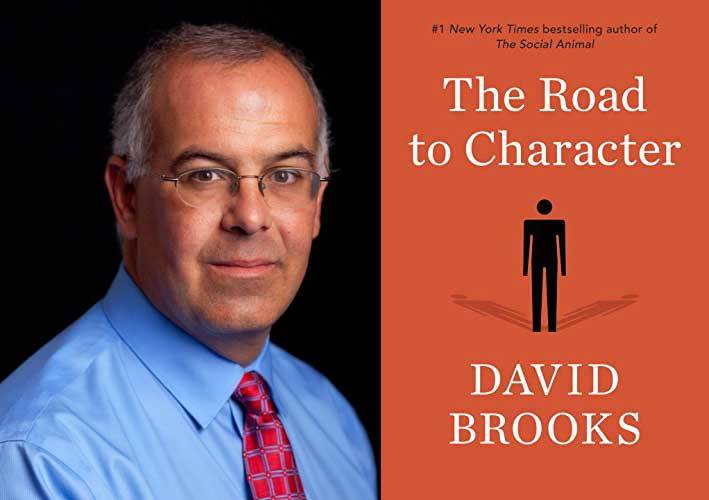

David Brooks is an op-ed columnist for the New York Times. He's one of the few conservative voices on the staff, although he's most concerned with traditional conservatism, i.e. the ethical project of taming the bad side of man's nature, than he is in parroting whatever it is that Fox News has to say at the particular moment. More often than I've ever actually sought out to read a David Brooks essay of my own free will, I've seen him quoted indignantly on my Facebook or Twitter timeline, with the caption, "Ugh, did David Brooks speak again?"

From the little that I've skimmed in the New York Times, he seems like someone with deep-held values who really knows what he's talking about when it comes to a traditional perspective on ethics, morals, and values. So, when it came time to select my fourth book from the Georgetown library, I thought, "Why not? Let's take the plunge."

"The Road to Character" is a collection of short biographies of people who have made a name for themselves in history in some way. Politicians, writers, Catholic saints. What they all have in common is that they lived pretty difficult lives and had to overcome very daunting obstacles. Brooks posits that it is the crucible of life's hardships themselves that is like a fire that burns away ethical flaws like materialism and selfishness. It is the crucible of life's hardships that inspires us to live a life that chases after higher goals and achievements that will leave a lasting positive impact on our lives and on the lives of the other people around us.

I like the fact that Brooks advocates for conservative values without ever invoking abortion, gun control, or any of the other hot-button issues that you might see on Fox News or CNN. Conservativism isn't about Fox News or CNN. Conservatism isn't about Donald Trump, or whoever the president is at any given time. Conservatism is not even necessarily about the Republican Party. Conservatism is about caution. It's about recognizing that together with man's potential for good, he is also born with something of a fallen nature: the yetzer hara in Jewish theology or original sin/ the natural man in Christian theology.

It's a good thing to promote freedom in society, and it's great that in America we have a society that is perhaps more free than any other society in human history. But freedom ought to be exercised with caution, recognizing that, left undisciplined, it's been the tendency throughout history for man's unpleasant nature to overpower and overwhelm his capacity for good.

Society benefits, at the very minimum, from taking time to develop leaders who are willing to follow the path in Brooks' book--to follow the road to character. It would be ideal if everyone in society was committed to living "the good life," but that is not realistic or fair to expect. Part of living in a free sociey is recognizing and accepting that people are free to live whatever kind of lives they want to, whether or not you personally accept their values.

Freedom is good. Freedom is okay. Still, a conservative is a conservative because he believes that, whatever the other classes of society may do, it is important for the leaders to follow certain timeless patterns of moral development to attain good moral character, so that they can go out and lead the others. Otherwise, the whole democratic experiment is going to fall apart.

I definitely recommend reading this David Brooks book, "The Road to Character," or any of his others. It helps you to understand the intellectual context of his New York Times articles and what he's really talking about when he talks about being a conservative. He means something that may overlap with but is not necessarily synonymous with whatever comes out of the mouth of President Trump. For example, in his most recent NYT op-ed article, "The Third-Party Option," dated July 30, 2018, Brooks writes about ways that he currently sees other in society better exemplifying conservative values than President Trump is doing.

He writes: "Across the country, power is being most-effectively wielded by civic councils--organically formed groups of local officials, business leaders, neighborhood organizations. The members may have different racial, class, and partisan identities, but they have one shared identity--love of their community."

Brooks' observation is very similar to the conclusions that I have been forming in my twenties. As I get older, I care less and less about the drama of national politics and more about being a responsible member of my community. I try to be a good member of my house of worship, I try to vote in local elections for candidates I resepct, and I try to be involved in local nonprofits, time permitting. Sometimes I feel a bit lonely as a conservative who cares more about values than about talking points, but Brooks helps me realize that I'm exactly where I need to be and doing exactly what I need to do.

My favorite part of this book was his discussion of the life of Frances Perkins, one of the members of President Dwight Eisenhower's cabinet. At one point in her life, Perkins was invited to become a Cornell University professor. "The job paid about $10,000 a year, scarcely more than she had earned decades before as a New York Industrial Commissioner, but she needed the money to pay for her daughter's mental health care.

"At first, she lived in residential hotels during her time in Ithaca, but she was then invited to live in a small bedroom in Telluride House, a sort of fraternity house for some of Cornell's most gifted students. She was delighted by the invitation. 'I feel like a bride on her wedding night" she told friends. While there, she drank bourbon with the boys and tolerated their music at all house. She attended the Monday house meetings, though she rarely spoke. She gave them copies of Baltasar Gracian's, 'The Art of Worldly Wisdom,' a seventeenth-century guidebook by a Spanish Jesuit priest on how to retain one's integrity while navigating the halls of power. She became close friends with Allan Bloom, a young professor who would go on to achieve fame as the author of 'The Closing of the American Mind.' Some of the boys had trouble understanding how this small, charming, and unassuming old lady could have played such an important historical role."

This passage makes me again feel like I am right track -- on the road to character. I am very fortunate to have had the chance to live and work in the same Cornell frat house: Telluride House. My first job after college was to come to Telluride and help design a special Cornell summer course, hosted at the frat house, on the topics in black studies, art history, and modernism.

I should feel both humbled and honored that my path in life intersects so closely, so far, with the lives of the great people Brooks desribes in this book. I ought to appreciate and make good use of the special opportunities that I have been given, and I ought not to let other people's choices, good and bad, distract me from my own personal route on the road to character.

From the little that I've skimmed in the New York Times, he seems like someone with deep-held values who really knows what he's talking about when it comes to a traditional perspective on ethics, morals, and values. So, when it came time to select my fourth book from the Georgetown library, I thought, "Why not? Let's take the plunge."

"The Road to Character" is a collection of short biographies of people who have made a name for themselves in history in some way. Politicians, writers, Catholic saints. What they all have in common is that they lived pretty difficult lives and had to overcome very daunting obstacles. Brooks posits that it is the crucible of life's hardships themselves that is like a fire that burns away ethical flaws like materialism and selfishness. It is the crucible of life's hardships that inspires us to live a life that chases after higher goals and achievements that will leave a lasting positive impact on our lives and on the lives of the other people around us.

I like the fact that Brooks advocates for conservative values without ever invoking abortion, gun control, or any of the other hot-button issues that you might see on Fox News or CNN. Conservativism isn't about Fox News or CNN. Conservatism isn't about Donald Trump, or whoever the president is at any given time. Conservatism is not even necessarily about the Republican Party. Conservatism is about caution. It's about recognizing that together with man's potential for good, he is also born with something of a fallen nature: the yetzer hara in Jewish theology or original sin/ the natural man in Christian theology.

It's a good thing to promote freedom in society, and it's great that in America we have a society that is perhaps more free than any other society in human history. But freedom ought to be exercised with caution, recognizing that, left undisciplined, it's been the tendency throughout history for man's unpleasant nature to overpower and overwhelm his capacity for good.

Society benefits, at the very minimum, from taking time to develop leaders who are willing to follow the path in Brooks' book--to follow the road to character. It would be ideal if everyone in society was committed to living "the good life," but that is not realistic or fair to expect. Part of living in a free sociey is recognizing and accepting that people are free to live whatever kind of lives they want to, whether or not you personally accept their values.

Freedom is good. Freedom is okay. Still, a conservative is a conservative because he believes that, whatever the other classes of society may do, it is important for the leaders to follow certain timeless patterns of moral development to attain good moral character, so that they can go out and lead the others. Otherwise, the whole democratic experiment is going to fall apart.

I definitely recommend reading this David Brooks book, "The Road to Character," or any of his others. It helps you to understand the intellectual context of his New York Times articles and what he's really talking about when he talks about being a conservative. He means something that may overlap with but is not necessarily synonymous with whatever comes out of the mouth of President Trump. For example, in his most recent NYT op-ed article, "The Third-Party Option," dated July 30, 2018, Brooks writes about ways that he currently sees other in society better exemplifying conservative values than President Trump is doing.

He writes: "Across the country, power is being most-effectively wielded by civic councils--organically formed groups of local officials, business leaders, neighborhood organizations. The members may have different racial, class, and partisan identities, but they have one shared identity--love of their community."

Brooks' observation is very similar to the conclusions that I have been forming in my twenties. As I get older, I care less and less about the drama of national politics and more about being a responsible member of my community. I try to be a good member of my house of worship, I try to vote in local elections for candidates I resepct, and I try to be involved in local nonprofits, time permitting. Sometimes I feel a bit lonely as a conservative who cares more about values than about talking points, but Brooks helps me realize that I'm exactly where I need to be and doing exactly what I need to do.

My favorite part of this book was his discussion of the life of Frances Perkins, one of the members of President Dwight Eisenhower's cabinet. At one point in her life, Perkins was invited to become a Cornell University professor. "The job paid about $10,000 a year, scarcely more than she had earned decades before as a New York Industrial Commissioner, but she needed the money to pay for her daughter's mental health care.

"At first, she lived in residential hotels during her time in Ithaca, but she was then invited to live in a small bedroom in Telluride House, a sort of fraternity house for some of Cornell's most gifted students. She was delighted by the invitation. 'I feel like a bride on her wedding night" she told friends. While there, she drank bourbon with the boys and tolerated their music at all house. She attended the Monday house meetings, though she rarely spoke. She gave them copies of Baltasar Gracian's, 'The Art of Worldly Wisdom,' a seventeenth-century guidebook by a Spanish Jesuit priest on how to retain one's integrity while navigating the halls of power. She became close friends with Allan Bloom, a young professor who would go on to achieve fame as the author of 'The Closing of the American Mind.' Some of the boys had trouble understanding how this small, charming, and unassuming old lady could have played such an important historical role."

This passage makes me again feel like I am right track -- on the road to character. I am very fortunate to have had the chance to live and work in the same Cornell frat house: Telluride House. My first job after college was to come to Telluride and help design a special Cornell summer course, hosted at the frat house, on the topics in black studies, art history, and modernism.

I should feel both humbled and honored that my path in life intersects so closely, so far, with the lives of the great people Brooks desribes in this book. I ought to appreciate and make good use of the special opportunities that I have been given, and I ought not to let other people's choices, good and bad, distract me from my own personal route on the road to character.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed