|

It's my thirtieth birthday! Sort of as a birthday gift to myself, I have a new website at alasdairekpenyong.com. Check it out. It's a paid site so I'm not sure how long I'll keep it up, but it would be nice to try and have a site in my own name.

0 Comments

So, jeez, wow. It's been four years since I started this blog.

I remember when I started the blog. It seems almost like yesterday, but it was four full years ago. I was 25. Squarely at the middle of my twenties. The second half of my twenties has seen a lot of adventure. I told myself, once back then, that when I was 30 I was going to be on Wall Street. I'm not on Wall Street, but I have a pretty nice job as a data analyst for Utah State University. It's great experience and it could serve me well, whether I want to stay at USU or even try to transfer into something finance or Big Tech related later. I turn 30 in a month. I want my 30s to be excellent. Here's hoping First of all, shout out to my new friend Adam for the inspiration to write my first blog post in ten months. He's so smart and went to BYU and Harvard and is a super great influence on me.

He shared the ten best books he’s read in 2020, and that inspired me to try to do the same. I did my “five best books of the summer” back in 2018, and I’ve been reading a lot, again, this year, so I’m excited to share. No particular order, except the order to which these things came to mind. I'd also like to invite you, reader: to share the 10 best books you read in 2020. (1) Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory by Ian Hacking This book explores multiple personality disorder, also known as dissociative identity disorder, from a critical mental health or history of science perspective. This means that instead of giving primacy to the assumption that the mental health patient is inherently disordered or wrong, Hacking places some of the burden of responsibility on the psychological profession to provide their claim to authority. Thomas Kuhn and Michel Foucault are two examples of writers who have documented the ways in which subjective cultural assumptions have become elevated to the level of scientific fact, repeatedly throughout history. Before we allow anyone to make us afraid of someone with multiple personalities—or with any other state of mind—we need to first make that person prove to us that what they’re saying can be trusted as real, objective truth, rather than private opinion raised to the supposed level of truth. Often, psychology is not capable of actually meeting that standard, so it’s important that we take a lot of what psychologists have to say with a grain of salt. I had the opportunity to study this book with a bunch of really, really, really smart people—I’m in a reading group made mostly of British psychologists and psychiatrists. I’m there as sort of a representative of the lived experience peer leadership community. I don’t have a psychology degree or anything even close to it, but life’s circumstances have put me in a position where it’s critically important for me to keep abreast of the discussions psychologists are having—to try my best to understand, whether I fully understand or not—because eventually, my developing understanding of leadership is going to mean that I’ll have an opportunity or a responsibility to speak the language of psychological discourse as best as I can, in order to make cogent, logical arguments to help protect people who are not necessarily in a position to be able to make these arguments for themselves. A few days after I finished the book and had the group discussion with the British psychologists, it was a little surreal to be presented with the opportunity to actually put in to practice all this leadership practice effort I had been working on. I had a conversation with a psychologist who is probably a global expert on my condition, borderline personality disorder, but who wagered her thoughts on some issues, multiple personality disorder and gender diversity (trans and enby experience). She was mildly familiar with trans experience, but really not familiar with enby people or the idea that identity could exist outside of a traditional gender binary. She proposed that people who claim to inhabit multiple sites of gender identity suffer from multiple personality disorder. I was able to deliver some really, really, really cogent arguments explaining to her why these ideas were not correct—and introducing her to the world of how Bernie-style millennials and Generation Z people talk about and philosophize about the minutiae of gender and sexuality innovation on their Tumblrs and similar spaces. I explained to her that I really wouldn’t expect a successful mid-career psychologist to be living her life based on what kids in their early 20s have been discussing on Tumblrs, in what is essentially the dark web, but that I would appreciate it if she listened to me and took me seriously as she heard me present some ideas to her for what was possibly the first time in her life she was ever hearing them. She did. Books can create really magical experiences when they teach you something new or open up new experiences of the world to you. Rewriting the Soul was one such book. One core argument that I remember was that it was medieval Catholic theologians—Thomistic theologians—who really introduced the idea of a unitary soul into Western civilization. Classically, there were many multipartite or multimodalistic models of the soul that were the foundation of Western society, let alone Eastern and other non-Western societies. So there is so much that we are erasing when we try to call it a disorder to have multiple personalities. The Entropy System, on Instagram and YouTube, is one great example of about how people with multiple personalities are representing themselves in liberatory manner, if you’re interested. (2) We Had No Rules by Corinne Manning This was a great book of lesbian, bisexual, and pansexual short stories. Notable because every story had a woman or a feminine character as the protagonist. The stories were powerful and compelling—truly 21st century fiction. My favorite story in the selection was “Ninety Days,” a novel featuring a breakup between a lesbian couple. The person who initiated the breakup did so because he realized that he was a man and didn’t feel like it was possible to continue to feel fulfilled in a lesbian relationship. He breaks up with her at the start of the story, and the remainder of the story tracks the other partner’s struggle to come to terms with her ex’s gender. She plays the role of the narrator of the story, and the pronouns that she chooses to use to describe her ex change throughout the story in tandem with her developing ability to understand what he told her about his gender. Someone close to me told me that she was impressed with the effort I put into learning about enby gender expression, and this story is a big part of why I take it so seriously. One day I hope I may get a chance to read it aloud with her. I may also be writing an essay about it for a nonprofit called Beyond Binary Legal. I’ll keep you posted. (3) The Swimming-Pool Library by Alan Hollinghurst This was really confident, powerful gay fiction. Not really much more than this to say. Read this book if you want to feel confident and powerful about being gay, bisexual, or pansexual. If you want to realize that the threads of gay, bisexual, and pansexual culture run very deeply through human history and that you have a lot to be proud of if one of those terms defines you. I listened to this book on audiobook while working with an amazing personal trainer (@60day6pack on Insta) to lose fifty pounds. It healed my soul even as the exercise healed my body. (4) The Deviant’s War by Eric Cervini I had the chance to actually talk to Dr. Cervini in March, April, or May, very early during quarantine. He decided that he was going to make a book and movie club to help us pass the time and boredom of what it felt like to be cooped up inside our houses. I submitted a committed to the first book club discussion and he featured it on his Facebook Live video. It felt awesome. The Deviant’s War is a great story about some of gay history prior to Stonewall. Dr. Cervini is a very, very, very talented Harvard and Cambridge trained historian. He’s younger than me, and he’s already done so much. I read this book on the beach in Delaware, Joe Biden’s state, while spending my birthday week with my best friend Nick. (5) Miles Gone By by William F. Buckley This is William F. Buckley’s autobiography. It is so beautiful. It articulates conservative values and the love for what is beautiful about America without ever being polemical or even explicitly political. He came to Alta, Utah, to ski sometimes when he was alive, and I enjoyed his descriptions of his trips to Utah. (6) The Conjure Woman by Charles Chesnutt I had the opportunity to work at Sewanee: The University of the South this semester as a digital humanities consultant. My boss there actually wrote her PhD thesis partially on this book. It’s an amazing representation of postbellum Southern culture. It honestly blows my mind. Significant parts of the plotline involved freed black persons speaking in the capacity of a narrator, filling pages and pages in the 19th century version of Ebonics or African-American Vernacular English script. I actually struggled to read the script because of how non-traditional the grammar and punctuation was, but my boss could amazingly read it quite fluently. I don’t think I’ve ever had an experience of modernist English innovation like that since I read James Joyce’s Ulysses as a teenager. I listened to about half of the audiobook while driving up to Idaho for Thanksgiving dinner. It made the drive really beautiful. (7) I Have Something To Tell You by Chasten Buttigieg Chasten just tells a really good, special story of his experience of coming out and finding his truth as a gay man. I would love to give his book to teenagers in middle school. I wrote down something about Chasten talking about North Faces being part of his high school experience, and how similar that was to the role that North Faces played in my own high school too. (8) The Future of the Professions by Richard Susskind This book asserts that emerging technologies are going to completely redefine society until we no longer recognize it anymore. These changes mean that, among other things, the nature of professional life is going to be deeply structurally redefined in the years to come in the 21st century. I’m excited by the new future Susskind describes. I’ve enjoyed spending time thinking about what my role in this new economy is going to be. I had one idea—and that idea has, thankfully and probably, been erased. So I’m looking forward to going back to the drawing board and thinking further about what my role could potentially be in this changing global economy. One prospect that’s been opened up to me is that if I want to I can spend my 30s learning how to become a very talented data scientists. That feels awesome. I’m just finishing up a data science/ computational literary studies analysis of The Official Preppy Handbook that I’m about to email to Lisa Birnbach, the author of the book herself and that I’m quite proud of. I used Python to do the analysis. I never thought that I would possibly be able to do something like this, but here I am doing, amazing 21st century things. (9) I, Robot by Isaac Asimov This book explores what ethics are going to look like in a future where robotics are a more extensive part of society than they are right now. It makes a fascinating, good, humanities style introduction to the very complex issues that lie before us in terms of artificial intelligence and its role in the 21st century. Here is a link to President Trump’s December 2020 executive order about the role of American and Constitutional values in tempering the boundaries of artificial intelligence. (10) The Book of Mormon: Journal Edition translated by Joseph Smith, Jr. Bette and Wynn, two of my favorite people, gifted this special version of the Book of Mormon to me for Christmas 2019. It really has become one of my most treasured possessions, and when I threw out the majority of my books in April 2020, this was one of the books that I made sure to keep. The purpose of the book is to invite you to feel what Latter-day Saints call the Spirit by pondering and meditating on the things you’re reading in the Book of Mormon as you’re reading them. You can use the extra space in the margins to write the thoughts that come to you as you’re reading the Book of Mormon. This will include your own thoughts, presumably, and perhaps, also, God’s thoughts too. It’s going to be really interesting to observe what my relationship to the Book of Mormon is going to look like in my 30s as a Jew, but depending what your interpretation of Jewish law is, I’ve been Jewish since about 2002, and I was Jewish throughout BYU, and I had a relationship to the Book of Mormon there, too, so maybe there’s a very long, dynamic conversation between me and God that’s about the happen in the 2020s. I had a very powerful experience of the Spirit, as I understand, very recently, while studying Moroni 1:4 (1:4, not 10:4), a verse about the importance of keeping written records for future generations to read. I told my friend Braden how excited I was about the Spirit, and I also told him other cool stories about the Fruit Heights 10th Ward, how cool it is up there, and how much fun it is and how much I learn every time Bette and Wynn invite me to attend the ward. Braden is this super cool guy who’s about to live on his mission to the Philippines. I think really highly of him, and I’m really glad I met him. He seems to really have a lot to say, and it almost sort of scares the people who are responsible for the pluripotentiality of my BYU friends losing their ability to take the Book of Mormon seriously. With whatever kind of a vote I have in society, I vote very strongly in favor of Braden’s right to continue to develop his talents, express his voice, and change the world. I also vote really strongly in favor of him as a person. I hope he has a fun time on his mission, a fun time in college afterward, and a fun time in literally whatever he chooses to do in life. Becoming his friend has been one of the best parts of my 2020. Here's an example of a recent verse Braden shared on social media: “No weapon that is formed against thee shall prosper; and every tongue that shall rise against thee in judgment thou shalt condemn. This is the heritage of the servants of the Lord, and their righteousness is of me, saith the Lord.” - Isaiah 54:17. I told him that it was a really awesome verse, and I tried to comment on what it might mean for him as best as I could. I remember in high school when people used to make fun of the Isaiah 50-something chapters at the lunchtable; I actually just hung out with one of those kids again last night a Hanukah party. So it's really special that Braden's able to make Mormonism makes sense to me in a way that makes me feel comfortable talking about Isaiah 54 with him; maybe one day I'll find the words to explain to him why that was a cool moment for me, but also, maybe people in Generation Z don't need to be experts on all the minutiae of all the ridiculous things millennials in Baltimore did during the 2000s. I'm going to recommend the movie "Yes, God, Yes," to him, having just watched it myself on Netflix, but he's going to have to, as my ex-girlfriend Caroline told me, "use [your] imagination." Something that we learn in the Park City, Utah, synagogue, is to be very proud of your Judaism. It's a paradox. We are at once members of this fancy, wealthy synagogue in this city that everyone around the world thinks is so special. At the same time, when it comes time to actually recite the blessings, like very simply traditional Jewish blessings, many people in the congregation stumble over their Hebrew in ways that are at best cute and at worse, embarrassing. Many people do not know how to say the full blessing over the wine, someone completely butchered the blessing over the Hanukah candles last night, and the rabbi accidentally ended the service early forgetting to stage the blessings over the bread and over the wine entirely. But it's this Judaism, this come-as-you-are Judaism, that you should be proud of. I put Braden's name in Mi Shebeirach last night because he's being bullied by people literally over twice his age right now, and that is not okay. Also put in other people's names, like Miki Forsting, Mrs. Solomon, and some of my roommates. I'm proud that my Judaism includes conversations with Braden about Isaiah in the 2020s just like it included conversations with Jon about Isaiah in the 2000s. It's hard to open even the first page of the Book of Mormon without being confronted with words indicating that God, Heavenly Father, Avinu Malkeinu, cares about each of us very much. So, let's be happy, and enjoy the last three weeks of this beautiful year that Avinu Malkeinu has given us: 2020. This is a piece of trash that I found from the Salt Lake City Abercrombie & Fitch before it closed down forever in early 2019. It was just some marketing that they had up on the shelves, but I found it beautiful, and as they started to dismantle the whole store, I took this piece for myself as a memento. It's beautiful. Trash, maybe, in some people's eyes, but one day they will come around and see that I was right and that it was beautiful, just like with everything else.

I promised myself I would start posting again when I got a computer, so this post is long overdue. Plus, this blog finally shows up near the top of the page when you Google my name, which was what I intended when I first made this website three years ago. Now that I have an awesome new Mac, it's time to post an update of my life.

So, what is my life like right now? I'm a grad student at Syracuse's online program for a master's degree in library science. During college, at BYU, getting a job as a student librarian was something that kind of got my life organized and worked really well. I spent most of my last two years there working as a reference librarian. I'm thinking that becoming a librarian at this stage of my life will have the same effect as it did during college. It's just a nice, solid career that is an undebatable fit for my personality and my talents, and I think it will be a good fit as a long-lasting career choice. I enjoy my classes, and I've enjoyed getting to spend some time shadowing one of the UVU librarians this semester. I could actually end up using my art history degree as a librarian. Right now, I'm working on a fifty page portfolio project describing how a librarian would help an art history student research Iraqi contemporary art. Taking contemporary art was a great experience at BYU--I had written my term paper back then on some of the art that is featured in the Salt Lake City airport. I'm on track with Syracuse to finish around Labor Day 2021. I'm working for Goldman Sachs in the CIMD department, which stands for Consumer and Investment Management Division. It's not quite IBD, which is what I was shooting for and hoping for when I was at Georgetown, but it's still a great division within a great company. I help out with Marcus, which is GS' relatively new consumer banking program. My title is specialist, which is even lower than analyst right now. It's all service, no sales, so I don't have quite as much pressure on me as I did when I was at Wells Fargo. One option that I have is to stay with Goldman for a long time and just keep progressing within the company. Maybe my library science degree would just be something to say that I have. I took a survey once that asked what my highest level of education was, and I wished so badly that I could put master's degree, just to say that I had one. Or maybe I could transition to becoming some kind of business librarian after spending many years at Goldman. The second option I have is to just get a librarian job right away and to treat Goldman Sachs as something that I'm just doing to put food on the table while I get through school. I'm not even close to making a decision on that yet. Hmm, I just did a Google search and found that there are actually Goldman Sachs librarians, like corporate librarians. I'll have to do some networking eventually because that could be a good avenue for me. If you're looking through my blog, I guess you're going to scroll down and search around a bit and see my entries from 2017-2019 describing the whole odyssey of my time at Georgetown. I enrolled in a Master of Science in Finance program there. I got straight A's my first year and became the class president. I got a 710 on the GMAT, which is 91st percentile. I did very well there for a while, and I enjoyed life and my experience of it. Unfortunately, I wasn't able to graduate. It was a big crash that caused me a lot of distress in my life, and I feel like I have since regained almost all the weight that I lost during those years. But I'm going to lose the weight again, and I'm back in graduate school trying again. I'm currently reading William F. Buckley's autobiography, Miles Go By. I'm rooting for Pete Buttigieg in the Democratic primary, and sometimes I wonder if I should switch parties. I don't know yet if I'm voting for Buttigieg or Trump. I enjoy watching Smallville and The New Pope on Hulu, and I can't wait for Elite season 3 to come out on Netflix in March. My favorite Billie Eilish songs are Bury A Friend and When The Party's Over. I stopped going to church in November. There was a Gospel Doctrine lesson about the book of Hebrews and how Judaism is fulfilled in the life and mission of Jesus. I realized that I didn't believe that Judaism has been fulfilled in Jesus and that no matter how much I found cultural comfort in Mormonism, there really was a change in my heart and in the way I see the world that happened when I received my mikveh and my bais din. Talking to a Jewish guy I met on Tinder is my main practice of Judaism right now, haha, but I want to make teshuvah in a deeper way with time. I feel awkward going back to Temple Har Shalom or Congregation Kol Ami, and those are pretty much the only two shuls in Utah besides Chabad, so I think my formal reconnection with a synagogue will happen when I move to another state in a year or two. I'm not really into doing mitzvot right now, but I think I can at least set a goal of reading Eichmann Interrogated and a couple of novels by Philip Roth over the next year or so. My rule, when I first started this blog, was to try and put a picture of me with every post. This is a pic of me with Congressman John Curtis, from September, to keep up the pattern. I briefly interned for the Congressman in Provo this fall, although I had to terminate the internship and start working again. I've gained weight, unfortunately, and it shows in the picture. I'm also including a photo of myself from one year prior to that, doing a headstand and showing off my CrossFit. I gained a lot of weight out of sadness over the end of Georgetown, and the difference between the two pictures reflects that. I'm back in CrossFit now, and back on the paleo diet, and hopefully I'll get back to looking the way I did at my prime again. My body is really weird right now. I think a body looks worse if it had previously been in shape and gains weight than it would have looked if it had always been heavy from the get-go. Book Review--"Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk" by Edward LiPuma and Benjamin Lee8/2/2018 When I was in high school, one of my most formative educational experience was the National High School Model United Nations (NHSMUN). Every spring, after a full year of preparation, we got to sit in the actual UN building in New York City and debate and deliberate as if we were actual countries' delegates. Whether sitting on the UN's most powerful committee, the Security Council, or sitting on a less powerful committee, we learned to see each of our national identities as something that was in some way subordinate to this international body of power.

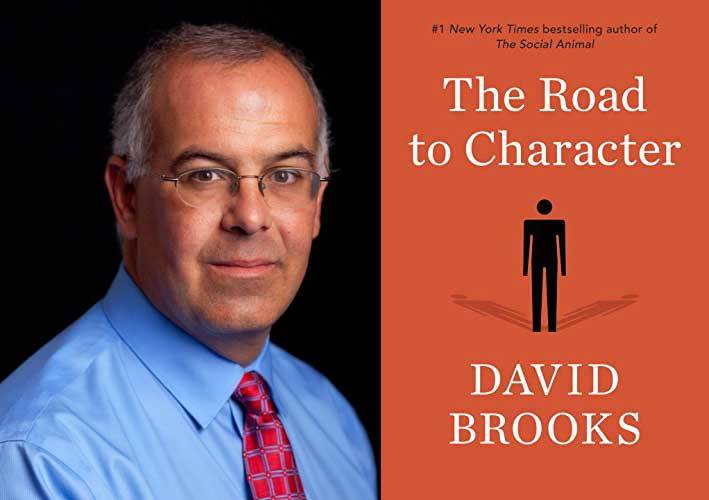

There was a time in history when the UN itself was a new invention. In response to new economic and political challenges following the end of World War II, world nation's leaders helped to establish first the League of Nations and then the United Nations as we know it today. Although the UN did remove some degree of national autonomy and sovereignty from each member country, it did still have the benefit of concentrating political power in a visible, fixed location. Even the poorest Third World nation, which did not have the gravitas of nations like Russia, China, and the US, could at the very least send delegates to observe any UN meeting it wanted. Any nation in the UN could physically keep abreast with any economic or financial decisions being made that might affect the flow of capital to the nation, its people, and its economy. In "Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk," the authors race the displacement and subordination of the UN and other postwar systems of international order--known collectively as the Bretton Woods system. Starting in 1973, the authors assert, visible international financial decision-making has been replaced by less-visible, supranational financial power, exercised through organizations like the OECD and the IMF. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system consolidated cash flow and the flow of capital decisively in the consumer and investor nations of the Global West while disenfranchising the producer nations of the Third World. "For those who like to mark transitions with dates, the year 1973 seems to be the significant turning point, the period when the fulcrum of power and profit began to shift from the production of commodities to the circulation of capital. In that year the destabilization of global currency markets (culminating in the collapse of the Bretton Woods system) interacted with a host of other historical events to create an economic and political force endowed with its own direction and momentum. The transformative end that hastened processes already in motion was OPEC's embargo on the export of petroleum and the ensuing escalation in energy prices, followed by price increases in other goods that precipitated a period of stagnation and inflation. "Before the embargo, the price of petroleum on world markets hovered around $3 per barrel of crude, but by the time the decade had come to a close oil prices had surged by a factor of thirteen to $39. Oil producers opted to denominate petroleum prices in US dollars; this compelled every oil-dependent nation (except the United States) to obtain dollars, and in very significant amounts, through the foreign exchange market. Especially for emerging states, this precipitated an enormous transfer of wealth from oil-dependent nations to OPEC members. Recycling petrodollars was essentially a process by which the current account surplus of OPEC financed deficits in nations that imported petroleum. According to the then-conventional and now discredited wisdom--encapsulated in the OEC's (in)famous McCracken Report (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development 1977)--OPEC would deposit its titanic surplus in the international money markets, where it would then be recycled through the global banking network, ending up back in the hands of what, at the time, were called the LDCS, or less-developed countries. The economic mantra was that privatized global financial markets would restore economic equilibrium by selling their excess funds to emerging nation-states, thereby allowing them to obtain petroleum in exchange for debt. "There was, however, no logical or institutional reason why global money markets should recycle petrodollars according to humanitarian principles of social fairness or justice. As World Bank records would later underline, for the remainder of the decade the net flow of capital to developing countries was actually negative, even as G-7 nations absorbed somewhere north of $150 billion per year. Without access to the capital surplus of petroleum producers, developing and transitional nations could generate the precious foreign exchange they needed to purchase oil only by forgoing other, non-oil imports, including the capital equipment needed to sustain employment and productive output. Among other things, the free market model of international finance apparently forgot that bankers are loath to buy a stream of short-term variable funds--the tens of billions of dollars of OPEC revenues held as short call deposits--and then extend long-term fixed rate loans under any conditions, let alone to economically strapped and already indebted countries. Predictably, international capital markets would furnish balance-of-payments financing only to countries they deemed credit-worthy, which essentially excluded much of the postcolonial world. That the advanced industrialized nations actively colluded in dividing up almost all the available capital meant that the negative consequences of the worldwide net capital deficit fell mainly on the shoulders of those who could least afford it. Thus, the recirculation of petrodollars gave postcolonial nations their first introduction to a form of political violence so abstract and mediated that its structural dynamic remained all but invisible" (pp. 67-69). The authors proceed to explain options, futures, swaps, and other key financial derivative instruments in the post-Bretton Woods financial system. As they do so, they raise concerns about the ways that the derivatives market consolidates cash flow and the flow of capital in the nations of the global West at the expense of Third World nations, who find cash flow increasingly tight and capital increasingly scarce. The "political violence" of the financial derivative market is the fact the visible, accessible financial decisions of Bretton Woods are no longer particularly visible or particularly accessible, even as their felt impact becomes more and more consequential in the lives of Third World populations. After reading this book, I'm definitely inspired to take more time to learn more about what life is like in the Third World. Most of the books I checked out from the Georgetown library this summer deal with the lifestyle, economy, and attitudes of the global West. It's fine to be passionate about learning more about the immediate culture where I live, but I feel a responsibility to learn more about the lives of people in the Third World--lives that seem to get more and more difficult as Americans' and Europeans' lives get easier. Future books on my reading list include the remainder of David Brooks' writings, anything by Harvard president emeritus George Eliot, and the novels of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Photo: "Chicago Board of Trade II" by Andreas Gursky David Brooks is an op-ed columnist for the New York Times. He's one of the few conservative voices on the staff, although he's most concerned with traditional conservatism, i.e. the ethical project of taming the bad side of man's nature, than he is in parroting whatever it is that Fox News has to say at the particular moment. More often than I've ever actually sought out to read a David Brooks essay of my own free will, I've seen him quoted indignantly on my Facebook or Twitter timeline, with the caption, "Ugh, did David Brooks speak again?"

From the little that I've skimmed in the New York Times, he seems like someone with deep-held values who really knows what he's talking about when it comes to a traditional perspective on ethics, morals, and values. So, when it came time to select my fourth book from the Georgetown library, I thought, "Why not? Let's take the plunge." "The Road to Character" is a collection of short biographies of people who have made a name for themselves in history in some way. Politicians, writers, Catholic saints. What they all have in common is that they lived pretty difficult lives and had to overcome very daunting obstacles. Brooks posits that it is the crucible of life's hardships themselves that is like a fire that burns away ethical flaws like materialism and selfishness. It is the crucible of life's hardships that inspires us to live a life that chases after higher goals and achievements that will leave a lasting positive impact on our lives and on the lives of the other people around us. I like the fact that Brooks advocates for conservative values without ever invoking abortion, gun control, or any of the other hot-button issues that you might see on Fox News or CNN. Conservativism isn't about Fox News or CNN. Conservatism isn't about Donald Trump, or whoever the president is at any given time. Conservatism is not even necessarily about the Republican Party. Conservatism is about caution. It's about recognizing that together with man's potential for good, he is also born with something of a fallen nature: the yetzer hara in Jewish theology or original sin/ the natural man in Christian theology. It's a good thing to promote freedom in society, and it's great that in America we have a society that is perhaps more free than any other society in human history. But freedom ought to be exercised with caution, recognizing that, left undisciplined, it's been the tendency throughout history for man's unpleasant nature to overpower and overwhelm his capacity for good. Society benefits, at the very minimum, from taking time to develop leaders who are willing to follow the path in Brooks' book--to follow the road to character. It would be ideal if everyone in society was committed to living "the good life," but that is not realistic or fair to expect. Part of living in a free sociey is recognizing and accepting that people are free to live whatever kind of lives they want to, whether or not you personally accept their values. Freedom is good. Freedom is okay. Still, a conservative is a conservative because he believes that, whatever the other classes of society may do, it is important for the leaders to follow certain timeless patterns of moral development to attain good moral character, so that they can go out and lead the others. Otherwise, the whole democratic experiment is going to fall apart. I definitely recommend reading this David Brooks book, "The Road to Character," or any of his others. It helps you to understand the intellectual context of his New York Times articles and what he's really talking about when he talks about being a conservative. He means something that may overlap with but is not necessarily synonymous with whatever comes out of the mouth of President Trump. For example, in his most recent NYT op-ed article, "The Third-Party Option," dated July 30, 2018, Brooks writes about ways that he currently sees other in society better exemplifying conservative values than President Trump is doing. He writes: "Across the country, power is being most-effectively wielded by civic councils--organically formed groups of local officials, business leaders, neighborhood organizations. The members may have different racial, class, and partisan identities, but they have one shared identity--love of their community." Brooks' observation is very similar to the conclusions that I have been forming in my twenties. As I get older, I care less and less about the drama of national politics and more about being a responsible member of my community. I try to be a good member of my house of worship, I try to vote in local elections for candidates I resepct, and I try to be involved in local nonprofits, time permitting. Sometimes I feel a bit lonely as a conservative who cares more about values than about talking points, but Brooks helps me realize that I'm exactly where I need to be and doing exactly what I need to do. My favorite part of this book was his discussion of the life of Frances Perkins, one of the members of President Dwight Eisenhower's cabinet. At one point in her life, Perkins was invited to become a Cornell University professor. "The job paid about $10,000 a year, scarcely more than she had earned decades before as a New York Industrial Commissioner, but she needed the money to pay for her daughter's mental health care. "At first, she lived in residential hotels during her time in Ithaca, but she was then invited to live in a small bedroom in Telluride House, a sort of fraternity house for some of Cornell's most gifted students. She was delighted by the invitation. 'I feel like a bride on her wedding night" she told friends. While there, she drank bourbon with the boys and tolerated their music at all house. She attended the Monday house meetings, though she rarely spoke. She gave them copies of Baltasar Gracian's, 'The Art of Worldly Wisdom,' a seventeenth-century guidebook by a Spanish Jesuit priest on how to retain one's integrity while navigating the halls of power. She became close friends with Allan Bloom, a young professor who would go on to achieve fame as the author of 'The Closing of the American Mind.' Some of the boys had trouble understanding how this small, charming, and unassuming old lady could have played such an important historical role." This passage makes me again feel like I am right track -- on the road to character. I am very fortunate to have had the chance to live and work in the same Cornell frat house: Telluride House. My first job after college was to come to Telluride and help design a special Cornell summer course, hosted at the frat house, on the topics in black studies, art history, and modernism. I should feel both humbled and honored that my path in life intersects so closely, so far, with the lives of the great people Brooks desribes in this book. I ought to appreciate and make good use of the special opportunities that I have been given, and I ought not to let other people's choices, good and bad, distract me from my own personal route on the road to character. Book Review--"Old Money: The Mythology of America's Upper Class" by Nelson W. Aldrich, Jr.7/30/2018 This was the third book that I read this summer. Understanding competing notions of wealth and class is especially important if I choose to pursue a career on the wealth management side of finance. A financial advisor or a private banker needs to understand what is at stake/ what is important in the lives of the families he is serving--as well as what is and stake and important in his own life and the life of his family.

Wealth management is a difficult task, if the goal is successful generation-to-generation wealth transfer, across multiple generations. It takes a very delicate combination of variables for a person to become rich in the first place, and preserving those variables into the second, third, and fourth generation is difficult, especially when the youth of younger generations become far-removed from the original social circumstances that made the ancestor so focused on success. It is the natural order of things for order to fade into chaos, industriousness to grey into sloth, and wealth to distill into poverty. As an example of the tendency for wealth to fall apart and decay across generations, Aldrich points out that "whatever wealth-generating enterprise it was that initially carried the family into history, the chances are that it did not continue under family management for more than the proverbial three generations. One study has shown that the attrition rate of family businesses in America -- enterprises, that is, for which there's evidence that the founder intended to pass them on to the next generation -- is about 80 percent in the first-to-second generation transfer, and again 80 percent in the second-to-third generation transfer." That is jarring. It means that only 4% of businesses started by a grandfather will successfully still be intact as a family possession by the time the grandson or granddaughter is ready to go and claim his or her inheritance. Old Money, as Aldrich defines it, is the collection of cultural practices visible and present among wealthy families who are trying to avoid the social casualty of business- and wealth-attrition from generation to generation within the family. Whether the family's wealth-preservation project fails or is successful, Aldrich classifies a family as Old Money simply for the fact of ever having once been wealthy and for trying, successfully or not, to preserve the financial and social legacy of that ancestor's success. The principal difference between Old Money and New Money, according to Aldrich, is the presence or lack of a concern for planned cross-generational wealth transfer, as opposed to excessive or inappropriate focus on the present generation's success in the market of earning and consumption. Whereas the key actor on the historical stage, for the New Money individual, is indeed he or she himself as an individual, the key world-historical actor for the Old Money individual is the family--deliberately engineered to stay healthy, functional, and successful in the generations to come. Quoting Charles W. Eliot, one of the past presidents of Harvard University, Aldrich writes: "The family, rather than the individual, is the important social unit. If society as a whole is to gain by mobility and openness of structure, those who rise must stay up in successive generations, that the higher level of society may be constantly enlarged, and that the proportion of pure, gentle, magnanimous, and refined persons may be steadily increased. New-risen talent should reinforce the upper ranks. … The assured permanence of superior families is quite as important as the free starting of such families." I think the understanding of wealth that this book presents is relieving, honestly. It takes some of the burden of achievement off my shoulders as an individual and distributes the load more fairly across the future generations of my family. After reading this book, I am increasingly less concern with finding the "perfect" job for myself. I'm more focused on finding a functional way to reach financial goals and benchmarks and then work with a financial advisor to set up financial and social instrument for the clean and effective transfer of that wealth to my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. The chief downfall or flaw in the Old Money project is probably the low success rate of the project. I keep thinking of that statistic, quoted above, that only 4% of family businesses are still owned in the family's possession by the time the grandson or granddaughter is old enough to go and claim it. What combination of school, adventure, cultural experiences, outdoor experiences, etc., could give a descendant who grows up in relative comfort, with all of his or her needs accounted for, the same kinds of discipline and height of character that was necessary for the ancestor to be able to earn and manage his or her wealth in the first place? Aldrich spends the remainder of his book, "Old Money," trying to answer precisely this question. Photo credit: "American Dream" by Sean Gale Burke. This is the second book I read this summer. I was very excited to check it out from the Georgetown library.

"Jews Queers Germans" is arranged like a series of hundreds of short stories one after the other. I found it hard to keep track of all the characters' names, but to be honest, you don't need to know the characters' names in order to understand this novel. The point of the novel is to show you, beyond any point of possible doubt, that there is a period in history from about 1890 to 1945 called "modernism." And, during modernism, beyond any point of possible doubt, many, many men were bisexual and homosexual. Whether bi or gay, they were normal people just like you and me. They were educated and uneducated, athletic and nerdy, rich and poor, powerful and disenfranchised, ethical and unethical, heroic and villainous. And in case you don't believe me, here are hundreds and hundreds of pages of true historical stories to prove it. It was really important for me to read this book this summer. I've been in the process of realizing that I am bisexual, and I needed some kind of resource to help me understand what I was feeling. Utah has a very strong heterosexual culture due to the influence of the state's predominant religion--The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also known as the Mormon church. Utah also has an unexpectedly strong gay culture because of all the gay Mormons who are struggling to express themselves and fight for their dignity in a political environment that very much resembles a theocracy or a religious ethno-state. When I was a college student at Brigham Young University, you could go to church any Sunday or even go to a religion class on campus during the week and learn the ins and outs of how to have a healthy straight marriage or relationship. You could also go to the university's gay-straight alliance and learn a lot about how to accept your gay identity, how to come out of the closet, and how to find a new sense of deeper meaning and purpose in life as you realize that Utah's dominant religion really does not have a healthy or psychologically-tenable place for you in its plan of salvation. There is a preponderance of gay and straight culture in Utah, and in the world as a whole. What you don't see so much of is the presence of a public bi culture, so that bisexuals can learn about themselves and live with as much confidence and cultural belonging as their straight and gay peers. So, books like "Jews Queers Germans," which devote hundreds of pages to giving the reader models and examples of bisexual thinking, are very important. A new term that I learned this summer is "biphobia." I was in a relationship, or a very special friendship, whatever you want to call it--Duberman's characters use both words--that struggled and ultimately failed because of a strong degree of internalized biphobia in both of us. I would like to see the world as a place where biphobia is just as unacceptable of a prejudice as anything else is. Hopefully this book review is a start. I really like what Wikipedia has to say about biphobia, so I'm just going to do down the Wikipedia article on biphobia, paragraph by paragraph, and lay out some important points. First, the actual definition of biphobia: "Biphobia is aversion toward bisexuality and toward bisexual people as a social group or as individuals. It can take the form of denial that bisexuality is a genuine sexual orientation, or of negative stereotypes about people who are bisexual (such as the beliefs that they are promiscuous or dishonest). People of any sexual orientation can experience or perpetuate biphobia." Second, there are multiple kinds of biphobia. Not everyone is biphobic in the same way, just like not everyone is bisexual in the same way. One form of biphobia is called "heterosexist biphobia." This is the view "that heterosexuality is the only true or natural sexual orientation. Thus anything that deviates from that is instead either a psychological pathology or an example of anti-social behavior." Another form of biphobia is called "binary biphobia." This "stems from binary views of sexuality: that people are assumed monosexual, i.e. exclusively homosexual (gay/lesbian) or heterosexual (straight). Throughout the 1980s, modern research on sexuality was dominated by the idea that heterosexuality and homosexuality were the only legitimate orientations, dismissing bisexuality as 'secondary homosexuality'. In that model, bisexuals are presumed to be either closeted lesbian/gay people wishing to appear heterosexual, or individuals (of 'either' orientation) experimenting with sexuality outside of their 'normal' interest. Maxims such as 'people are either gay, straight, or lying' embody this dichotomous view of sexual orientation." A third form of biphobia is called "bisexual erasure." This includes the belief that people have to be equally attracted to one gender as much as the other in order to be bisexual. This erases probably 90% of the bisexual population, who actually do prefer men or actually do prefer women. Bisexual erasure also includes the idea that only women can be bisexual, but men cannot be. Bisexual erasure further includes the idea that "that bisexual behavior or identity is merely a social trend – as exemplified by 'bisexual chic' or gender bending – and not an intrinsic personality trait. Same-gender sexual activity is dismissed as merely a substitute for sex with members of the opposite sex, or as a more accessible source of sexual gratification." In "Jews Queers Germans," men from all walks of European society participate in all kinds of variations of bisexual friendships and relationships imaginable, while their society around them struggles to keep up. Through the voice of the law, the military, the government, the scientific community, the academic community, and the religious community, the protagonists encounter each of the three forms of biphobia that I have described above: (1) heterosexist biphobia, (2) binary biphobia, and (3) bisexual erasure. The novel doesn't really have a happy ending. Out of the 500 pages, I can't remember any of the friendships or relationships that actually worked out in a long-term way, like a heterosexual marriage--"till death do us part," or, in Mormon culture, "for all time and eternity." Dealing with loss and with separation is a part of human life. We ought not focus on fear of an end, missing all the beauty of the beginning and the middle. I used to believe in marriage for time and all eternity as the model for what perfect love looks like. I am a bisexual guy, who like many gay guys at BYU, came to realize that this story doesn't quite describe what I believe about the world. Most gay Mormons become secular, atheist, and agnostic, fed up with religion altogether because of the way they've been treated in Mormon culture. I am a religious person by nature, so it was important for me to find a healthy religious community when my Mormonism fell apart. I converted to Judaism this spring, after a year of study with my rabbi, and I've found עם ישראל to be a healthy, nourishing, supportive community in which to live my adult life going forward. Judaism is a pretty tolerant culture. I guess that explains why "Jews" appears in the title of this book. During the modernist period of history, from 1890 to 1945, some Germans believed that Judaism was promoting a too-tolerant view of love, sexuality, gender, and life in general. Various conservative German thinkers became to use Jews as a scapegoat for what they believed was the financial and moral degeneracy of their society. Judaism has been a part of my life informally since I was about twelve, so at this point, sixteen years later, Judaism means way, way more to me than just a safe place to be bi. But Judaism is a topic for another essay. Right now I'm more interested in talking about bisexuality and biphobia. If you could take one thing away from this book review, I would ask you to please realize that biphobia is a thing and to recognize that biphobia is hurting a lot of people's lives. "Jews Queers Germans" is a really hard book. It's not for everybody. But if you're interested in learning more about bisexual culture, maybe this is the right book for you. Oh, and since I always like to include at least one quote from the book, here is my favorite paragraph from the book: "His friendship with Rathenau having weathered assorted storms, Kessler calls on him at his house in Grunewald. He finds Rathenau sunk in gloom and attributes it in part to the Grunewald home itself, which he's always detested, once describing its décor--with more than a hint at his view of Rathenau's sexual proclivities--as a mix of 'petty sentimentality and stunted eroticism…as if a banker and a masturbating boy thought it up together.' But as Kessler well understands, Rathenau's depressed isolation is due to much more than the surrounding décor." The first book that I read this summer was "Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street." An ethnography is a first-person analysis of some group's culture, or subculture. To write an ethnography, you would enter the social group, hopefully in the most honest, straightforward, and polite way possible, and, with the group's consent, spend a couple months or years living among them and observing and participating in their habits and their overall culture.

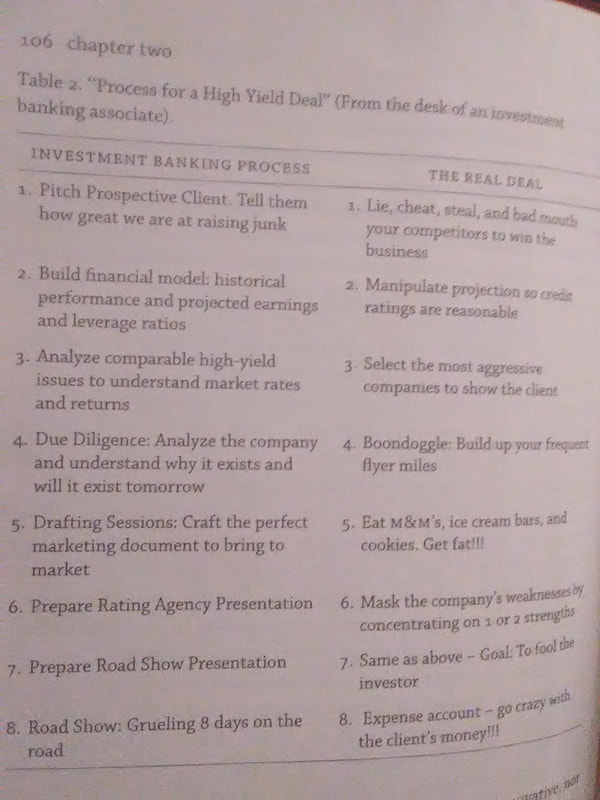

You're writing down the things you see and do. You're writing down how you felt as you said and did these things. You're interviewing other people in this group to see how they felt as they said and did the things. You're maybe throwing in a bit of history, where that context is relevant. And overall, most importantly, you're making connections between the different parts of the culture, drawing connections, identifying contradictions, and ultimately saying, "Hmm, well this makes a lot of sense," or maybe, "Hmm, this actually doesn't make that much sense to me." It's a cool way to kind of tell the story of a social group. You could write an ethnography about your college, an ethnography about your hometown, a ethnography of your lacrosse team, an ethnography of whatever. In this case, the author, Karen Ho, is trying to write an ethnography about Wall Street. She got a job as an employee at an investment bank on Wall Street, and, with their consent, she began writing down what she saw, finding connections and themes in the behaviors she was observing, and ultimately trying to decide whether Wall Street does or does not make sense, from her perspective. Her most memorable argument was the idea that many investment banking analysts are actually producing BS work, not real financial analysis. She includes, for example, the chart that I've copied here to this article, comparing the correct technical way to build a financial model and the actual way that she observed investment banking analysts producing models--as lazily and sloppily as possible. She writes: "While investment bankers certainly recognize that they do, in fact, bullshit their clients, they usually view such practices as justified by the hard work they genuinely put in, their superior knowledge of the market, and the financial good they are sure their interventions ultimately accomplish." Having never actually worked on Wall Street, it's difficult for me to agree or disagree with her statement about whether the work investment bankers do is actually BS. There's a big finance meme culture on Instagram and other social media forums, where you can see people making fun of the BS work that investment banking interns do seem to produce during their summer internship. But the general idea there is that it's only the interns, greenies, newbies who are doing the BS. The people making fun of them are the established associates, vice presidents, etc., who are actually producing real work and often correcting the mistakes and the BS that they observe the analysts putting forth. I would guess that Ms. Ho is of a left-leaning orientation. Her critique of Wall Street seems to be that, in contrast to Main Street, where people work 9 to 5, and put in a good, honest day of labor, Wall Street seems to be a place where BS, covered by elitism and fancy college degrees, passes for hard work and justifies a sense of cultural condescension toward Main Street American middle-class workers. How do I feel about this? Well I think Ms. Ho is mistaken. I think that finance is real, hard work, as I'm learning in my Georgetown finance program, and as anyone who tries to number-crunch a financial statement also knows. I think the best way to understand the financial world is not through a qualitative analytic method, like ethnography, but rather by quantitative methods, like getting in there and learning how to produce a multi-tab Excel spreadsheet valuation analysis, the same way Wall Street analysts might do. Once you get in there and learn how to work with the numbers as a financial analyst, I think you might have a little more respect for Wall Street and its parallels in other cities, and I think you might be a little more inclined to say that finance industry professionals do actually deserve to get paid the kinds of salaries they do. Finance is hard work. I can't pretend that I'm not haunted, sometimes, by the ghost of Karen's whisper, her suggestion that everything I might possibly do in my finance career is BS. Some finance roles and projects do seem more intellectually intense than others, and some roles and projects do seem closer on the spectrum to BS. But at the end of the day, I reject her claim that finance altogether is a BS industry, and I would argue pretty confidently that finance is just as hard or as valid of an industry as anything else anybody might choose to do. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed